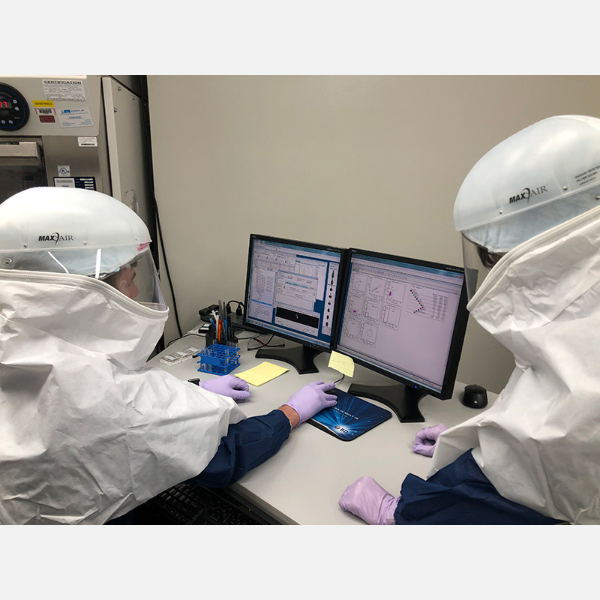

Germ fighter

As a youngster on a Wisconsin dairy farm, Shelly Krebs ’00 saw how microscopic organisms like germs and viruses affected her family’s dairy herd. That childhood interest in the unseen led to a career battling some of the most virulent pathogens and the search for a COVID-19 vaccine.

Currently, her research focuses on B cells, a key component of the body’s immune system.

Her group at the U.S. Military HIV Research Program seeks to isolate monoclonal antibodies, which bind to the virus and can be used to treat or prevent disease.

“We have produced (monoclonal antibodies) to HIV, Zika, and dengue, and are currently applying these same techniques to isolate (those antibodies) to SARS-CoV-2,” Krebs said. “In addition, we are developing a vaccine candidate that will go into Phase I clinical trials by this fall.”

She sees medical research — and its results — as crucial to protect individuals and society.

“I hope that COVID-19 has reinforced the need of vaccination with the public,” she said. “… Individuals in the United States don’t need to worry about the risk of death from smallpox, infant mortality due to rotavirus, or debilitating outbreaks of polio, for example. Our society has gotten so used to the benefits of vaccination that we no longer see the danger of these diseases.

“Research is like a puzzle, and scientists try to put all the pieces together through experimentation. I’ve always liked puzzles, and thinking of different ways to solve problems through logical reasoning.”

While STEM professions are moving toward gender equity, Krebs said progress largely depends on the area of study. “Engineering and theoretical mathematics are still largely dominated by men, while there is more of a balance in biomedical sciences. My graduating class at Dartmouth was dominated by women and the majority of the current team I work with is women and led by women.”

Studying at Bradley led to a research project with chemistry professor Michelle Fry as well as internships with the USDA and a cancer institute. After earning her doctorate in microbiology and immunology at Dartmouth Medical School, Krebs pursued fellowships and research projects in places like Sri Lanka, India and Liberia.

“(Internships) opened doors to my first job … and ultimately to graduate school,” she said.

Krebs noted her parents also inspired her. “Growing up on a dairy farm taught me hard work and tenacity. My parents rarely took a day off in 42 years,” she said. “I think about that a lot when I need to work late or through weekends or when faced with challenges. I’ve found that hard work and tenacity are two of the most important attributes to being successful in research. The ability to communicate effectively and resolve conflict are close seconds.”

The research required to battle the COVID-19 pandemic makes those traits even more critical.

“I have never before seen a scenario in research where there has been this much collaboration, coordination, urgency, or free exchange of information. It is humbling and inspiring to see the sacrifices these scientists are making, knowing that the only way to solve this crisis is by doing it together.”

— Bob Grimson ‘81