Caught up in the game

Imagine living so long that your memories become meaningless and the beautiful times of your life dissolve from pleasurable thoughts to nothing.

In another scenario, take on the guise of North Korean leader Kim Jong-un or one of his advisers and tackle life, and power, in that isolated nation.

Later, try to solve the newfound flooding problems in a rapidly growing and changing city at the turn of the 20th century.

Games offer all these experiences as well as boosting empathy and wreaking havoc on players’ emotions.

At a recent conference, game design instructor Tim Hutchings sat in on a session featuring participants playing artificial intelligences interviewing others taking human roles about their lives and work. Taking matters beyond Siri or Alexa, relationships developed and bonds deepened.

“At the end, you learn the artificial intelligences, the programs are over and we’re going to turn them off,” Hutchings said. “It’s intensely, agonizingly sad. I was in a room full of people weeping as these characters were saying goodbye.”

That’s because these types of games fulfill a mission beyond entertainment, he said. “Games aren’t just about having fun. They’re about having emotions, having experiences vicariously, about making hard choices.”

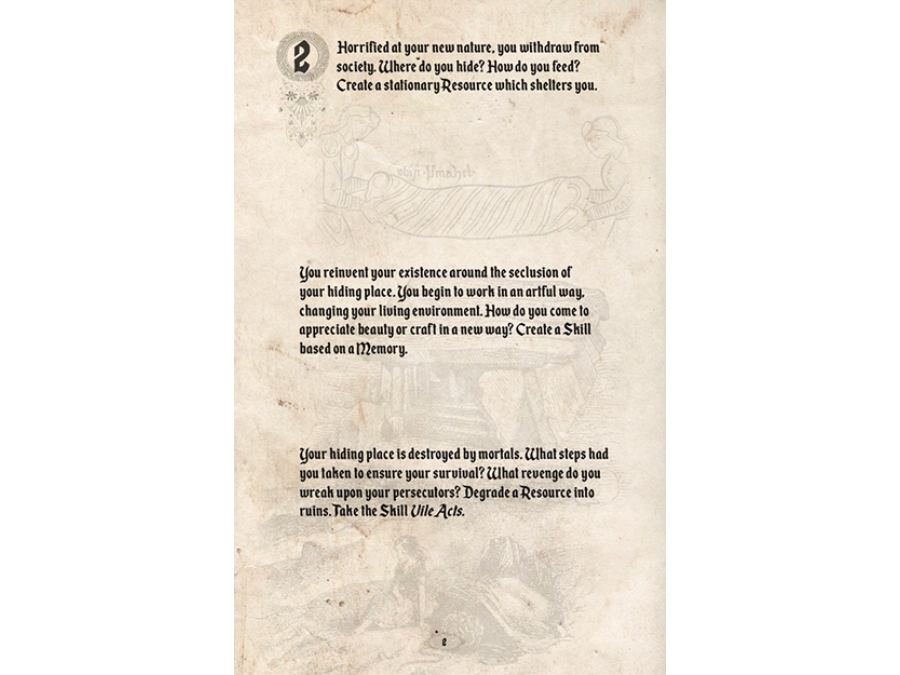

A designer of analog or tabletop games, Hutchings’ latest effort, Thousand Year Old Vampire, lets players chronicle the centuries of a vampire’s existence using an expansively illustrated book of prompts which allows for character development and journaling. The game is a solo one but can be adapted for more players.

“The game is specifically about ‘what does it mean to live so long that your memories fall away?’” he said.

He added choosing vampires allowed latitude. “Vampires are a very loaded cultural thing. It’s an easy subject for speculation. When I started thinking of being immortal, of time, of memory, vampires are an easy fit. Everybody likes vampires.”

Games can cover a range of characters and situations, from those based on science fiction to those featuring Roman legionnaires, soldiers in Vietnam, rebellious teens — even notorious dictators like Kim Jong-un or Adolph Hitler.

“In the game Dear Leader, people play him (Kim Jong-un) and his advisers,” Hutchings said, adding he consulted with defectors, government representatives and experts on North Korean geopolitics in crafting the game. “It’s a party game, meant to be really funny but hidden within it are horrific things about what it’s like to live in a dictatorship.”

Another of his games — The 1914–1915 Research Survey of the Los Angeles County River Basin — sounds like a scholarly treatise and, in fact, is based on academic works describing efforts at the time to deal with floods as that city grew.

“Designers seek out interesting moments of human interaction throughout history and then create games about those,” Hutchings said. “You can find this stuff anywhere.

“When we analyze what a game is, we can say it’s actions and events and all these different things. And those apply equally to digital and tabletop games but the two systems handle them differently. A lot of games can become empathy-generators where we will inhabit some other person for a while and maybe understand things through their eyes.”