Research on plus-sized women’s clothing in the early 20th century brings surprising insight to the world we live in today. | 10 min. read

When retail merchandising professor Carmen Keist was in high school, she loathed shopping for clothes with her friends. While they sifted through the latest fashions on the racks of Abercrombie & Fitch, American Eagle and The Limited, she found herself sidelined — they didn’t make clothing in the larger sizes she needed.

“My friends asked me why I wasn’t shopping, and I always came up with some reason that I didn’t want to,” she said. “I didn’t want to say, ‘I’m too fat.’”

Though there were a few plus-sized teen clothing stores at the time, shopping often felt lonely for Keist. So perhaps it’s no surprise that a moment that occurred years later while doing research for her master’s degree felt so fraught with emotion.

Keist, who had long loved both history and costume design, was flipping through a century-old needlecraft magazine at Iowa State University when she came across an ad selling a “stout women’s corset.” The ad stopped her cold. “I thought: ‘Wait a minute, they’re calling me stout!’”

Keist couldn’t get the ad out of her mind. In a turn-of-the century culture that celebrated whip-thin Gibson girls — thin, fashionable women drawn for magazines by artist Charles Dana Gibson — the options for larger women were scarce.

“I really started to think about living 100 years ago. What would I wear? Could I buy clothing? How would I look?”

That curiosity spurred a yearslong quest to understand the clothing choices and challenges of plus-sized American women of the early 20th century, from high fashion to everyday clothing.

While Keist’s research is unique — she is one of just two people in the world to zero in on these topics — its implications are vast. Her work has illuminated the bias that has threaded through our culture against larger women in the past 100 years and the real challenges these women faced as they tried to overcome it.

Her findings may even help explain some of the most insidious practices that fuel the plus-sized women’s clothing industry today — and the attitudes about larger women themselves.

“Plus-sized women have been marginalized, and these patterns have been in place for a long time,” said Keist. “We’re starting to realize that, and we’re also realizing that it doesn’t have to continue to be that way.”

It may seem as if our culture has always revered thin bodies for women, but that isn’t the case. Keist noted Lillian Russell, a well-known stage actress and singer in the late 1800s who was revered for her beauty and style, tipped the scales at 200 pounds.

“Then, (a larger body size) was connected to health and wealth,” said Teresa Drake, an assistant professor who teaches wellness and dietetics. She pointed out that when food wasn’t so plentiful and most people were doing hard physical labor — right up until about the 1900s — larger women had higher status.

But a flurry of changes around the turn of the 20th century began to alter attitudes. Scientists began to understand the links between calories, consumption and weight change. Bathroom scales were patented. It suddenly became much easier to measure and, to some extent, understand factors that led people to be larger or smaller. At the same time the Gibson Girl set the standard for an ideal woman.

Into this perfect storm came another advance: ready-to-wear clothing. Until the late 1800s, women mostly sewed their own wardrobes. But starting in about 1890, stores and catalogs began selling clothes that women could simply buy off the rack. While companies zeroed in on providing clothing options for average-sized women first, it wasn’t long before they saw opportunity to clothe the 13 million “stout” women who represented more than 10 percent of the American population.

If companies liked the idea of ringing cash registers that selling to these women represented, it didn’t mean they necessarily catered to their tastes, said Keist. Magazine features in Good Housekeeping might showcase the latest fashions in bright colors: rose, violet and yellow. Stout sizing, however, typically offered a smaller selection of dark colors that companies noted for their slimming effects.

Keist suspects not every larger woman was thrilled with the options. “It’s easy to imagine (being a plus-sized woman) going to the store and being so excited about a new, cool thing called ready-to-wear and then being so disappointed that the only choices are brown, blue and black,” she said.

And good luck finding clothes with embellishments as a larger woman: ruffles, folds, lace and embroidery, common trims for women at the time, were nowhere to be seen in stout women’s clothing. Instead, stout women typically chose from plain, more masculine styles.

By the time World War I rolled around, larger women weren’t just subtly encouraged to try to hide, or at least be embarrassed by their weight. They were told in no uncertain terms that their size was a detriment to the war effort. Keist noted a diet book author who advised women that they should “tell loudly and frequently to all your friends that you realize that it is unpatriotic to be fat while many thousands are starving.”

Brutal? Absolutely. But the other terms thrown around by fashion journalists and other writers of the time — that larger women were lazy, undisciplined and even smelly — aren’t so far off from the descriptors we still hear today. And outside the fat acceptance movement, fat is still a dirty word.

“It’s so negative,” said Keist. “If you want to make someone feel terrible about themselves today, the word you call them is ‘fat.’”

I really started to think about living 100 years ago. What would I wear? Could I buy clothing? How would I look?

Over time, our culture may have become more, not less, obsessed with size as American waistlines have expanded. A 2015 Washington Post article stated the average woman now weighs 166 pounds (up from about 140 in 1960). A year earlier, the medical journal The Lancet reported that 60 percent are overweight or obese, according to body mass index ratios. Men have made similar gains.

And while the most blatant body disparagement might have been scrubbed from our cultural conversation (it’s unlikely people will question anyone’s patriotism based on their weight) there’s no question that stereotypes and skepticism linger. And that leads to real and measurable differences in the way we treat larger people.

Keist said she still sees it in the apparel world. Women’s clothing sizes were typically separated by “average” and “stout” sizes in the early 1900s, and there continue to be distinct sections for average and plus sizes in retail stores.

“There’s a sense of separate but equal,” she said. “But a lot of people don’t want to be separated from others based on their size.”

That’s just the beginning: some older studies have shown that a third of all doctors associate obesity with traits including dishonesty and hostility. Research from 2004 by the National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance (naafa.org) found that in the world of work, larger people make about 6 percent less than thin people in the same positions. They’re also less likely than thinner peers to get promoted.

And while it’s true that obesity has been linked to strokes and heart disease, the correlation may not be as clear as scientists once believed. “Obesity is a risk factor for these different issues,” said Drake, “but some evidence suggests that it may not be the weight, but the stigma the person experiences as a result of their weight.”

For Danielle Glassmeyer, associate professor of English and coordinator of Bradley’s The Body Project, such statistics are devastating. What she believes may be even more destructive are the ideas that larger people internalize about themselves and how those make them act in self-sabotaging ways.

Almost 70 percent of women delay seeking health care because of their weight, according to a 2010 study published by the American Public Health Association. But it’s also more insidious than that.

“You don't want to live in the body you have–namely because societal stigmatization of having a larger body is so painful and discriminatory,” she said. “Negative attitudes towards ‘fat’ people are pervasive. The belief is that they are less intelligent, less medically healthy, less attractive — just less than all around.”

Even those who intellectually understand that people can be healthy at many different sizes sometimes don’t fully internalize that idea. Glassmeyer often speaks to students at Bradley’s Activities Fair and experiences it firsthand.

“I’ll be telling them about what The Body Project is — about the idea of body acceptance — and they know the ideas behind it so well that they’re finishing my sentences,” she said. “But the minute I finish talking, someone will say, ‘So, can you recommend a good diet?’”

Americans spend their lives in a world awash in bias and discrimination against larger people. But in recent years, there has been something of a sea change thanks to the body acceptance movement.

Plus-sized models are gracing the covers of magazines, while companies like Dove and clothing manufacturer Maurice’s are more inclusive about body size in their advertisements. In June, SELF magazine published a new editorial style guide that eliminated derogatory terms, e.g., spare tire or muffin top, along with other improvements.

Attitudes are changing on Bradley’s campus, too. At the Activities Fair, students can visit The Body Project table to learn about “the freshman 15” — the common (and sometimes anxiety-producing) perception that the typical student gains about 15 pounds during the first year of college. They learn that not only is the total weight gain a myth (studies differ, but for women, the average is about 7 pounds, and a bit more for men), but also that it should be expected. Both women and men who start college at 18 are still growing, a process that doesn’t stop until age 20 or even later.

Lisa Fix-Griffin, a counselor for Bradley University’s Health Center who has worked with people who have eating disorders for three decades, said she feels a shift in attitudes. “I have noticed that there seems to be less of a preoccupation with extreme thinness,” she said. “People are seeing that it’s not realistic or that it’s not something that they want. There is more acceptance of diverse, unique, natural human forms.” She also thinks body positivity blogs have helped introduce people to a different way of thinking.

Fix-Griffin’s anecdotal evidence lines up with larger research findings: according to a 2016 study by the American Psychological Association that looked at women’s attitudes about weight over the course of 30 years, women today are more accepting of their bodies than they’ve ever been.

For Keist, such changes are part of a revolution she’d like to see both in the clothes we wear and the ideas those clothes represent. She wants to see more clothing options not just for larger people, but for people of all sizes and abilities.

After all, for many, clothes are one way to express who they are and what they value. Clothes can be a way to make people feel confident on a job interview, attractive on a blind date or joyful on a night out.

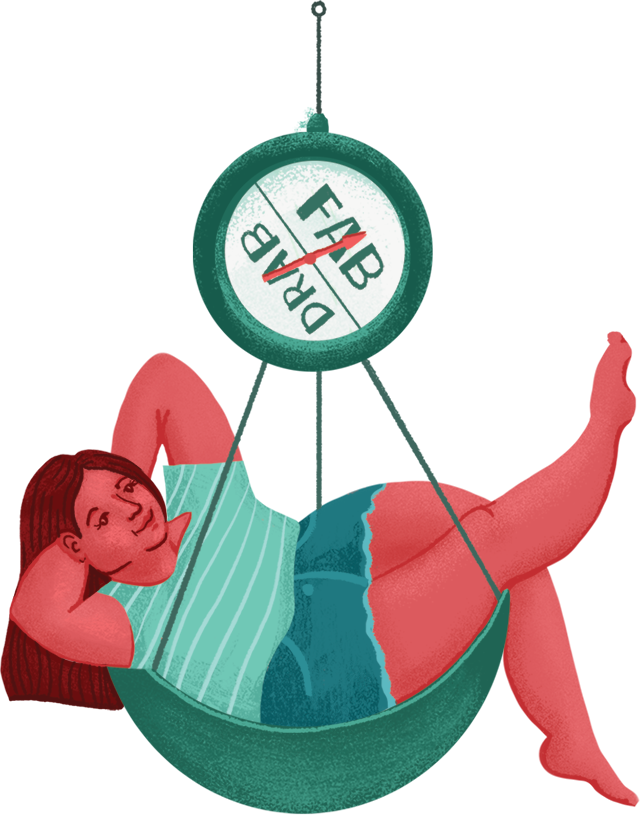

But when the clothing choices offered are uniformly drab, unflattering, or ill-fitting — because of the person’s size, or because they are in a wheelchair, or because they don’t have the manual dexterity to work buttons or zippers — it can feel crushing. “If you’re stuck in gray sweatpants because you don’t have other options, you might say: ‘I don’t feel good,’ or ‘I can’t be good.’” she said.

In a world in which body acceptance is growing, the clothes people wear should reflect the self-confidence they have, no matter what their size. Keist knows it’s well past time for us to find more ways to make beautiful, useful clothes for every body.

Post Your Comments