WATCH COMMENCEMENT LIVE ON SATURDAY, DECEMBER 14.

Livestream access begins at 9:15 a.m.

Capturing the biggest drug kingpin

of our day — Joaquin “El Chapo”

Guzmán Loera — became a career-defining

quest for JACK RILEY ’80.

This time, Ahab won. | 10 min read

Capturing the biggest drug kingpin

of our day — Joaquin “El Chapo”

Guzmán Loera — became a career-defining

quest for JACK RILEY ’80.

This time, Ahab won. | 10 min read

Not long after he started as the new special agent in charge of the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) duty station in El Paso, Texas, Jack Riley drove a lonely stretch of Interstate 10 toward Las Cruces, N.M. There were only six headlights providing illumination that night in 2007: those from Riley’s new Chevy Impala and the four from the large pickup and SUV tailing him.

He pushed down the accelerator and sped past 100 mph.

According to intelligence reports, Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera, the most successful and most dangerous drug lord of this generation, had put a $100K price tag on Riley’s head. With two hit men behind him, Riley knew he had to come up with a plan to save his own life and possibly his family’s as well.

“It just didn’t look right ... No one heads north that time of night. There’s nothing between El Paso and Las Cruces, except a couple of bulls*** gas-and-burrito exits.”

Pulling out his BlackBerry, Riley fumbled with the keyboard and called one of the agents who lived close to his neighborhood. After securing his family, he called his best friend, Tony, in Chicago who told him to get to the nearest police station.

“You don’t get it,” Riley told his friend. “I got 30 miles of desert on each side and these scumbags are on me. This isn’t Chicago where you drive a few blocks and you’re at a police station. There’s nothing I can do.”

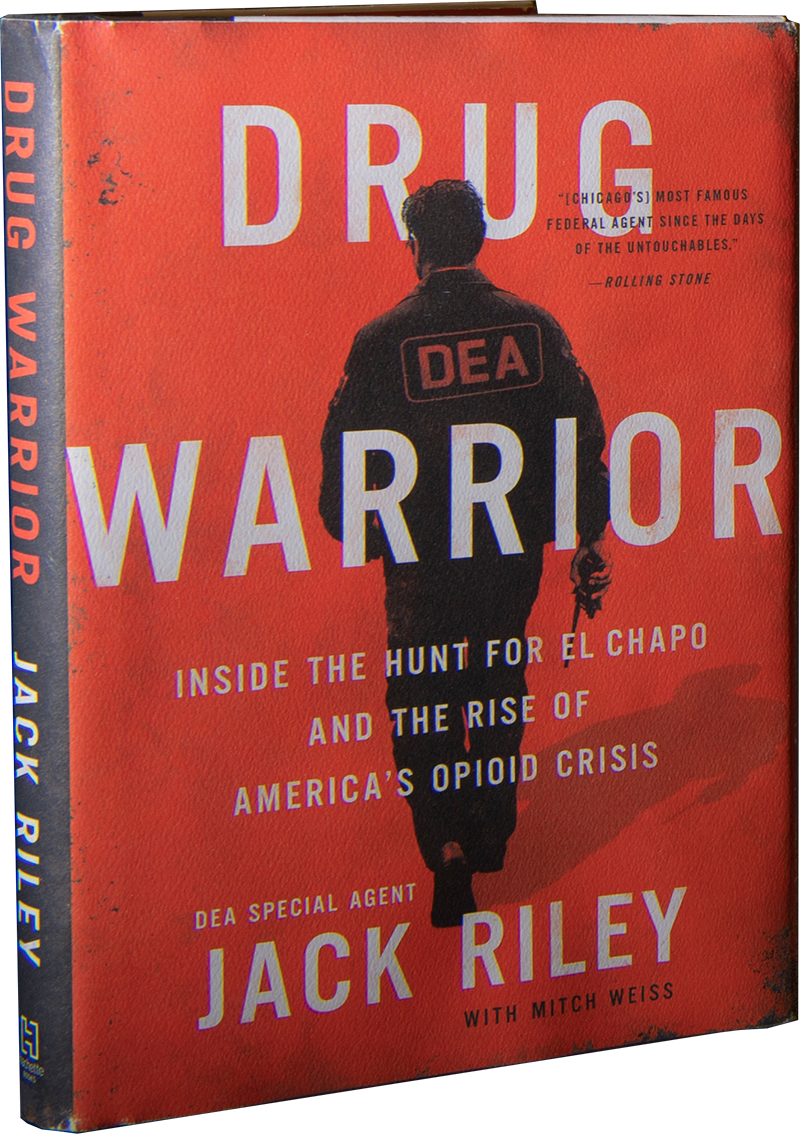

The scene above is from the opening of Riley’s book “Drug Warrior: Inside the Hunt for El Chapo and the Rise of America’s Opioid Crisis” (Hachette Books, 2018). Written with Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Mitch Weiss, it starts with Riley’s early days as an undercover agent in Chicago making small drug busts, and culminates with his role as the DEA’s second in command, overseeing global drug enforcement efforts.

“It’s partly my fault, I should have known better,” he said recently of the El Paso episode. “I wasn’t taking precautions even though I knew there was a threat.

“Obviously, I carry a couple of guns; I can take care of myself. But the point is, that was a different arena, and when you’re literally a half a mile across the border from Juarez, which is one of Chapo’s home turfs where he had probably killed 10,000 people in the last 10 years, you don’t really realize, yeah, these people can threaten you, but down here, they can actually pull it off.”

Chronicled in the book, Guzmán and Riley did this cat-and-mouse chase for the better part of the DEA agent’s 30-plus-year career. Part memoir, part crime drama, it’s a compelling look at the agency’s inner workings and how cooperation between law enforcement agencies ultimately led to El Chapo’s extradition and lifetime jail sentence.

Nabbing the drug lord didn’t just consume Riley, it became an obsession partly because he believed it was critical to national security. Riley blamed Guzmán for being the mastermind behind America’s current opioid crisis.

“He saw the prescription drug problem in the U.S., and he knew heroin was an opioid-based drug,” Riley said of El Chapo. “At some point the doctor stops giving prescriptions, you can’t buy it on the street, it’s too expensive; you can’t steal it from your grandmother’s medicine cabinet, what do you do? Well, you take that walk down the street and you buy cheap, high-grade, high-potency heroin and it supports your habit. (Guzmán) played right into that.”

When the agency first learned about El Chapo, its focus was on the Cali and Medellín cartels in Colombia, not Mexico. In the late 1980s, the DEA saw the Mexicans as smugglers, not narcotics traffickers. Riley said Guzmán changed all of that. Although he grew up in poverty and had little formal education, Guzmán had several mentors who were the country’s early drug traffickers.

“These people are mass murderers, no question, but he’s one hell of a corporate CEO. And many times, what you find with these guys, including terrorists, is it’s a fine line between them going bad or becoming just as successful legitimately.”

Since Guzmán’s imprisonment, new information has come to light. With his first escape from a Mexican prison in 2001, news reports said he bribed the guards into letting him leave in a laundry cart. Riley said they now know that Guzmán simply walked out the main door to a waiting car.

After his second escape in 2015, Guzmán may have had 3,000 to 4,000 of his rivals killed as soon as he was out, as evidenced by the mass graves found six months to a year afterward.

“He was constantly doing this,” Riley said. “It’s scary if you look at the numbers of just how he was able to accomplish it without government intervention. He was in everybody’s pocket, from the military to the police. I think in some cases all the way to the presidential palace. It’s mind-blowing to me. There were some estimates that he had $20-$30- $40 million a month going out just to pay bribes.”

Eventually, El Chapo’s belief in his own invincibility is what ultimately led to his downfall. “Burritos and porn are what did him in,” Riley wrote near the book’s finale. But while he is the most significant drug lord to date, even without El Chapo, Riley said Sinaloa is the No. 1 provider of narcotics to the U.S., possibly the world.

Rivals have rushed to fill the power gap, however, including the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, a powerhouse that’s far more violent than Guzmán. But Riley also believes Big Pharma and its relationship with Congress and the Department of Justice should be held accountable.

“If we could indict some of the corporate CEOs who knowingly and willingly go around regulations and laws, I don’t think they’d do too well in a Brooks Brothers suit playing kickball in the yard with the real felons. I think it would change the industry. I really think we have to strive to do that.”

We knew so much about him,

his habits, houses, his inner circle,

his tastes in food and entertainment.

Burritos and porn

are what did him in.

A television series based on the book is in develop- ment for the FOX Network. Riley said they hope to shoot the pilot in January and if it sells, the first season will have 22 episodes — mostly shot in Chicago — starting next fall.

“The first season is about supplying fentanyl to the Midwest,” he said. “It’s timely, and I think without giving up a lot of sources and methods, it gives you an inside look at how (DEA agents) have to start from a phone number and work up to indicting several hundred people in three to four countries.”

TV glamour aside, Riley is humble about his success. He called his wife, Monica, a saint for all she and their son, Kevin, endured. Riley also acknowledged that at his retirement, he was one of a handful of guys who were still married to their first wives.

“The divorce rate can be brutal on the job. The 13 transfers, too, got a little old. (Moving) wears on you and it wears on your family. Most of those moves were promotion related, so you’d get to the new place, you’d be excited, get right into the job and the social network, but your family had to start over in a new neighborhood, new schools, make friends and find their way around.”

Adjusting to retirement has been tough. Riley considers his colleagues the real heroes and said he was proud and lucky to have served with them.

“I did nothing by myself,” Riley said. “I was blessed. Like Chapo, I had great mentors. I had people who looked out for me and when my number got called I stood up and looked for those people to help me out.

“That’s the thing I miss the most. I miss the crisis, how when bad things happened we all rallied together and figured out, ‘How are we gonna win?’ That’s what I miss the most. I really do. I think that’s what keeps you ticking.”

Post Your Comments