JET Program: A Teaching and Cultural Exchange Opportunity in Japan

Nick Modine ’22 and Andrew Wilson ’22 experienced formative study abroad trips in Japan that prompted a desire to live and work there as adults. Modine’s hometown has a Sister City connection in Japan, while Wilson’s fiancé hails from the country.

Though they live in separate provinces almost 500 miles apart, the two new Bradley grads have achieved that goal by taking part in the Japanese Exchange and Teaching (JET) program, a coveted opportunity that has thousands of applicants every year.

Since its founding in 1987, JET has sent more than 70,00 participants from across the world, including more than 35,000 Americans, to work in schools and government offices throughout Japan.

Modine, who double-majored in political science and international studies at Bradley, teaches in Takamatsu, a city of nearly half a million on the southern island of Shikoku.

Studying in Japan during his junior year in high school sparked an interest in the possibility of living and working there after college.

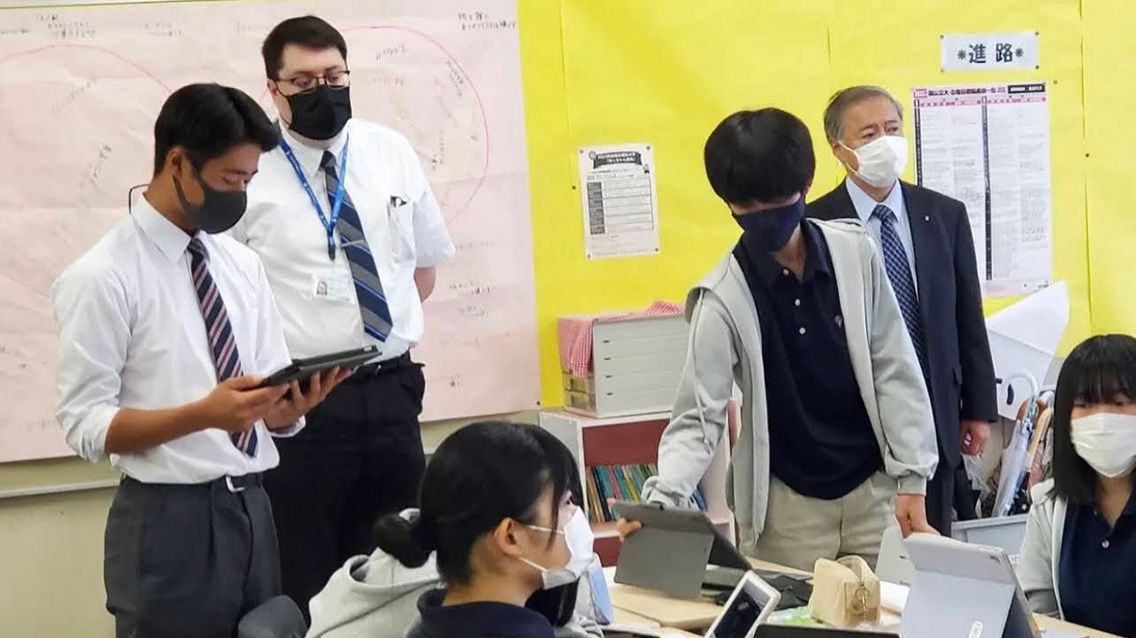

A double-major in history education and international studies, Wilson teaches at the Koei Veritas Junior and Senior High School in Matsudo, a city of half a million in the Chiba province just outside of Tokyo. The location turned out to be perfect since his fiancé lives in Ichikawa, less than 20 minutes away.

Both found inspiration to take the career leap across the globe from Bradley faculty. History professor Rustin Gates, a former JET participant himself, taught Wilson’s favorite classes and lent his name to Wilson’s application materials. Meanwhile, Modine received encouragement from philosophy and religious studies professor Daniel Getz, who lived in Japan and steered Modine toward the JET program as a potential postgrad option.

Much of their life unfolds in Japanese classrooms. Both Modine and Wilson are proficient in speaking Japanese, but it’s not a requirement. Speaking English to the students at all times is the unsaid expectation.

At Wilson’s school, students stay put in one classroom while the teachers move from room to room. He also noted students learn English differently in Japan, almost like a mathematical equation with the different component parts making up the whole of a sentence.

Modine has adjusted to a more significant departure from the American education system: Japanese schools do not issue detentions. Classroom management became more of a rhetorical challenge.

“You have to convince the kids to fix their behaviors by themselves,” Modine said

Wilson considers the teenage students he teaches remarkably similar to their American counterparts. Some are highly motivated; others aren’t as much. Some consistently chime in to participate during class time, while others watch YouTube on their iPads.

And he believes that extends to the overall cultural experience of living in Japan.

“We’re not that different, even though we’re on other sides of the world,” Wilson said.

— Thomas Bruch